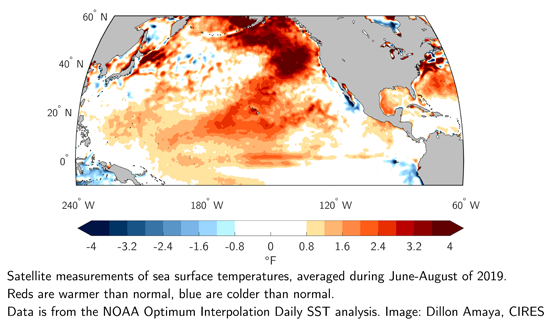

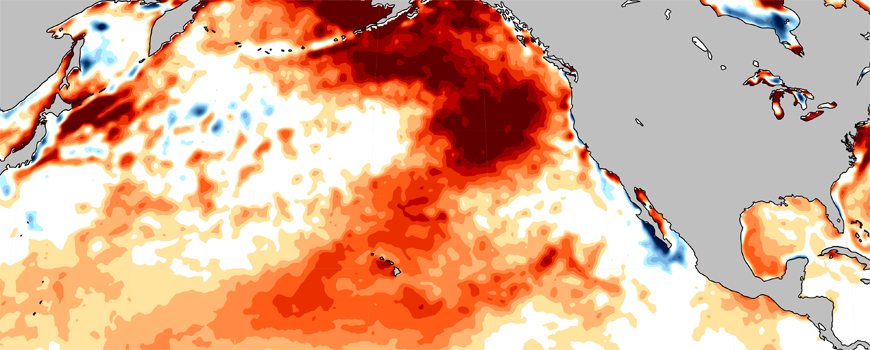

Researchers found weaker winds to be the most likely culprit for the record-breaking marine heat wave. When circulation patterns weaken, so does wind. With less wind blowing over the ocean’s surface, there is less evaporation and less cooling; the process is similar to wind cooling off human skin by evaporating sweat. In 2019, it was as if the ocean was stuck on a hot summer day with no wind to cool it down.

A thinning of the ocean’s mixed layer, the depth where surface ocean properties are evenly distributed, also fueled Blob 2.0, the researchers found. The thinner the mixed layer, the faster it warms from incoming sunlight and weakened winds. The impacts can keep accumulating in a vicious cycle: the lower atmosphere above the ocean responds to warmer water by burning off low clouds, which leaves the ocean more exposed to sunlight, which warms the ocean more, and burns off even more clouds.

Warm ocean temperatures have the potential to devastate marine ecosystems along the U.S. West Coast. During warmer months, marine plants and animals with a low heat tolerance are at higher risk than during the winter—heating already warm surface waters can be more harmful than warming colder waters.

“Although this warming does not hit during the important ‘spring bloom,’ it can potentially reduce the quality of food that many open-ocean and migratory species, like seabirds, turtles, and fish, rely on for growth and development as they forage over great distances off the North Pacific in the summer and fall periods,” said Art Miller, research oceanographer at Scripps and a study co-author.

With the changing climate, we may see more harmful impacts like this in years to come, the authors reported. As global warming continues, heat extremes like last summer’s Blob 2.0 are becoming increasingly likely.

“It’s the same argument that can be made for heat waves on land,” said Amaya. “Global warming shifts the entire range of possibilities towards warmer events. The Blob 2.0 is just the beginning. In fact, events like this may not even be considered ‘extreme’ in the future.”

Some other studies have suggested that under global warming conditions the subtropical ocean-atmosphere feedback that drives this type of summertime extreme ocean temperature in the midlatitudes will occur more frequently and with higher intensity, said Miller.

The researchers hope these results will help scientists and decision makers better predict and prepare for future marine heat waves. “If we understand the mechanisms that drove this summertime event and how it influenced marine systems,” Amaya said, “we can better recognize the early warning signs in the future and better predict how heat waves interact with the coast, how long they last and how destructive they might be.”

In addition to Amaya and Miller, study authors are Shang-Ping Xie at Scripps Oceanography and Yu Kosaka at the University of Tokyo.

This research was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, the National Science Foundation, NOAA, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, the Japan Science and Technology Agency through Belmont Forum CRA InterDec, and the Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology through the Integrated Research Program for Advancing Climate Models.

– Adapted from CIRES, University of Colorado Boulder

修改评论